The Family Tree

Family Tree Genealogy

We are first introduced to the idea of a family tree during childhood. It slowly becomes part of our identity as snippets of information are picked up – from family stories, old records, overheard conversations and heirlooms passed on from one generation to the next.

I began assembling a version of my own family tree in the 1970s. It was pieced together from inserts in old family bibles as well as books, diaries, letters and records kept by ancestors and their relations.

Ancestry.com

The Ancestry website was first launched in the late 1990s and I was an early user. At first, there were simply not enough people using it to make it particularly useful. That said, it was a convenient place to keep records – those that which may otherwise have been lost among all the papers and floppy disc collections lying around the office or in filing cabinets. Sharing did generate some surprises. Messages began to arrive from long lost relatives on my mother’s side of the family who had emigrated in the 19th century. Some had fought on the Union side during the American Civil War, others were in Australia; none in the UK. Folk over there were interested in their origins, not so much here. An interesting observation was that almost all wanted to be Irish, Scottish or Welsh, not English. I felt sorry in having to disavow them. In any case, there was not a great deal to say, our ancestral paths had diverged so much that we were now strangers to each other – we had been taught different histories in our schools.

23andMe

Then, in 2006, the genome hit the ground running. And what a change it made! No one among us big data analysts had expected that simply asking people to pay for something would be so much more successful than offering to pay them for the same thing. Initially, there was a surge of activity on the site which, as soon as family tress could be added, mostly helped Americans looking for their European or African roots. Several found me, and I was able to help them track down their heritage to small villages scattered around Lincolnshire and sometimes North Yorkshire. They themselves mostly lived in the American Mid West or around Ohio and, although looking for Coats of Arms, normally had to settle for photographs of gravestones or village churches. Their trees are still there on 23andMe’s companion family tree site MyHeritage, with ancient links to Kings, Lords and Knights and, yes, Coats of Arms. But big data, then as now, had its drawbacks – privacy. Recognizing its importance for health research, much of 23andMe’s ambition was focussed on tracking inherited diseases, until its impact on the Insurance industry was fully recognized. Today, it is heavily regulated, and most people are hesitant to make their genetic data public, not just because of its possible impact on themselves but also on their relations, particularly their children.

AncestryDNA

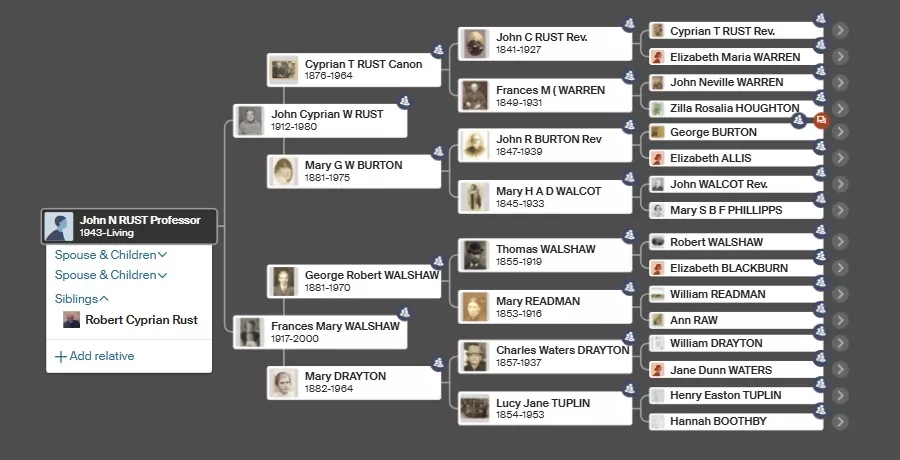

In 2012, AncestryDNA was launched as an add-on to Ancestry, and rapidly replaced 23andMe as the must-go-to site for family tree researchers. It was at once able to leverage the large existing Ancestry family tree database in combination with DNA from saliva samples to provide far more convincing evidence of relationships than either Ancestry or 23andMe alone. There were other searchers, of course – about paternity, birth parents, donors and donor siblings, and estranged family members. Within a few years, I was able to confirm the identity of all my 3XGreat Grandparents simply by tracing links to their other descendants.

The Meaninglessness of Genetics Beyond Five Generations

One of the most important insights I’ve gained is that beyond five generations, trying to trace genetic characteristics within a family becomes pretty meaningless. Each generation dilutes the genetic contribution by half: we inherit genes from two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, sixteen 2G-grandparents, thirty-two 3G-grandparents, and sixty-four 4G-grandparents. The descendants of these 4G-grandparents, who are of the same generation as us, are our fifth cousins.

I recently consulted ChatGPT on this, and it explained that, in the absence of cousin marriages, there’s about a 90% chance that I share no detectable DNA with my fifth cousins, and about a 35% chance of sharing none with fourth cousins. This is because we only have 23 pairs of chromosomes, and each generation involves a largely random shuffling of genetic material. The mathematics of probability theory tell us that the odds of inheriting the same DNA segment from a distant ancestor are slim.

So, what does this mean for those who boast of distant ancestral connections to kings, queens, or lords of the manor? The likelihood of sharing any meaningful genetic ancestry with them is practically zero, at least it would be without cousin marriages to keep those genetic links alive. And that’s where the theory fails, because cousin marriages do happen. In fact, when we consider distant cousin relationships, the answer to “how many nth cousins do I have?” is effectively “everyone”. All humans are related.

Genetic Relationships in Closed Communities

In a closed community, such as an English county or a small country, the degree of relatedness is far greater than most people realize. For instance, in my grandmother’s home county of Lincolnshire, the probability of two people being completely unrelated over just five generations is less than 2%. In such communities, nearly all marriages are between some level of cousins—whether that’s fifth, fourth, third, second, or even first cousins. Most of us don’t even know who our great-grandparents were, let alone our 4G-grandparents, so we remain blissfully unaware of these distant connections.

The Importance of Community and Ethnicity

This leads to a second important insight: communities and their histories shape our identities, particularly our ethnicities. The genetic variation within and between ethnic communities is a product of history—often shaped by migration, invasions, and mixing. Some populations, such as Africans, Indigenous Americans, or Australians prior to the colonial era, are genetically very distinct. Others, like the populations of Britain and Ireland, are far more closely related than most people realize.

For example, the genetic differences between the English, Irish, Scots, and Welsh are much smaller than the differences between those populations and the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, or Normans who invaded them. This close relatedness creates challenges for services like AncestryDNA, which struggle to define separate national identities within Britain. The results often blur the lines between regions: someone from North Yorkshire might be labeled as Scottish, while someone from central Scotland might be labelled as English.

This blurring isn’t entirely their fault. Services like AncestryDNA cater to customer expectations, particularly from American users seeking to disentangle their European roots. The result is often a compromise: genetic boundaries are drawn based on demand rather than scientific precision, which can muddy the waters for those genuinely trying to understand their ancestry.

While commercial DNA services might say “the customer is always right,” this approach often oversimplifies complex genetic realities. For those with mixed-race ancestry, identifying roots accurately can be profoundly meaningful. Unfortunately, pandering to simplistic European identities dilutes that purpose, even though from a business perspective meeting majority demand might seem essential. Their paying customers are seeking an identity – being an ‘Irish American’ or a “Scottish Canadian” or an Australian descended from a deportee to British prison colony, is important to them.

The future of genome-based family tree research

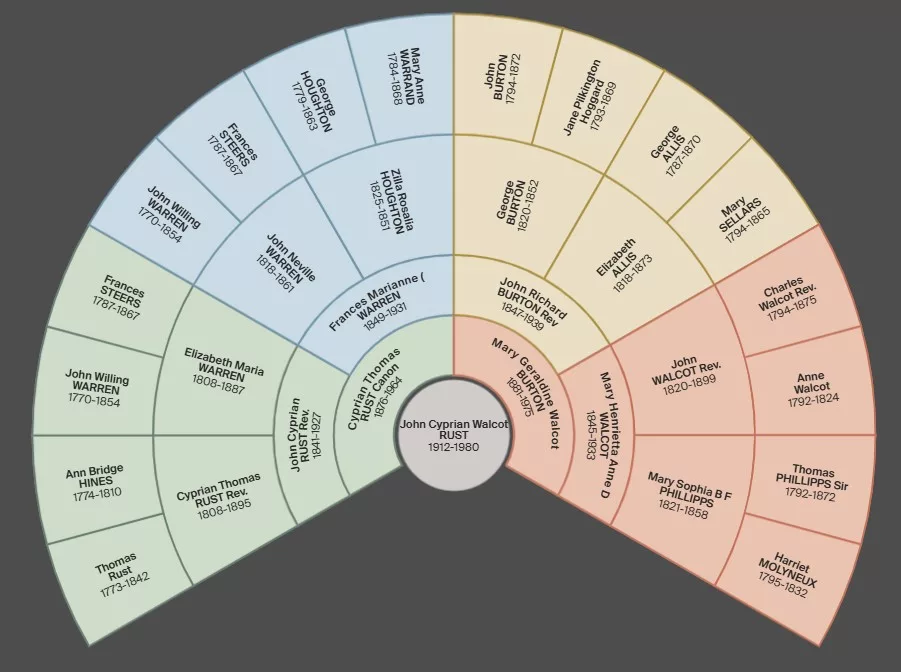

Both 23andMe and AncestryDNA are being challenged by the impact of privacy legislation following the revelations of the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018. Since then, Ancestry has deleted living relations from all public family tree databases, and this presents a problem as only the living are in a fit state to answer messages. Today, fellow researchers and internet users are far less likely to respond to queries from those not already among their friend group. For the record, here are some ancestor for my first cousins over five generations.